Dante began work on his magnum opus somewhere between 1304 and 1308, inspired by an idea he’d had for many years—immortalizing his unrequited love Beatrice for all time in a long, epic poem. Since the original manuscript isn’t known to survive, and Dante didn’t record his exact writing dates, all we have to go upon are hypotheses. Dante finished it in 1320 or 1321.

The oldest known manuscripts date from 1330, hand-copied in full by the great Giovanni Boccaccio. He didn’t copy them from the original, but from other copies.

After Dante’s death in 1321, the final section couldn’t be located, and there were no notes left behind with instructions for finding it. Then Dante appeared to his son Jacopo in a dream, showing him where the end of the manuscript was kept. Jacopo found it in that exact location!

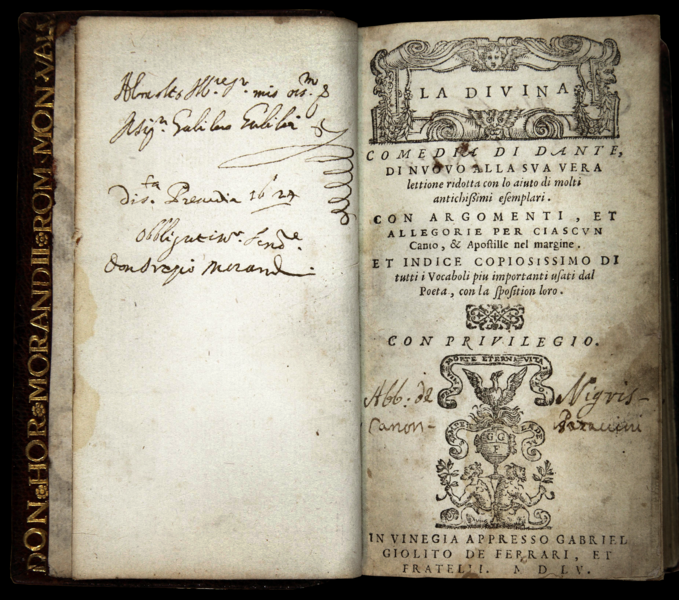

1555 Ludovico Dolce edition, owned by Galileo

The original title was simply Commedia (Comedia in Latin, as Dante identified the work to one of his friends). About 40 years later, Boccaccio first appended the adjective “Divine” to the title. The version pictured above marked the official first time the book was titled The Divine Comedy.

Many contemporary people are confused by the title, since it’s not what we recognize as a comedy in modern times. But historically, a comedy was a genre with a difficult start for the protagonist and a happy ending, written in everyday language.

The first printed edition was published in Foligno on 11 April 1472. Fourteen of the 300 copies are known to survive. The printing press is in Foligno’s 15th century Oratorio della Nunziatella (which is kind of like a chapel).

Venice printed the next edition in 1477, followed by Florence in 1481.

The book is divided into three canticles, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Each contains 33 cantos (i.e., a section of a long poem), for a total of 100, including the introductory canto. Most people count the first two cantos of each canticle as prologues.

Dante wrote in terza rima, three-line stanzas (tercets) with the rhyming pattern ABA BCB CDC. This was a poetic form he created, possibly influenced by the Provençal troubadours he so admired. Because Italian is such a poetic language, it’s easy to find natural rhymes for so many lines. It’s much more difficult in English, causing some translators to employ forced rhyme schemes.

Each canticle ends with the sweet, hopeful word “stars.”

Thirty-five-year-old Dante wakes up in the Wood of Error on Maundy Thursday 1300, no idea how he got there or lost the way so badly. Taking courage by the rising sun, Dante starts climbing the Delectable Mountain and presently encounters a female wolf (avarice), a leopard (lust), and a lion (pride). Dante turns back fearfully and comes face-to-face with another terrifying being.

Dante is ecstatic when the shadowy form identifies himself as Virgil, author of The Aeneid and Dante’s idol. Virgil says he was summoned by Dante’s lost love Beatrice, who’s desperate to save him before it’s too late. Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory, providing support, encouragement, and protection when Dante is afraid or overcome by emotions.

Dante encounters many famous people during his journey down through the nine circles of Hell, some of whom he personally knew. Each circle holds a different type of sinner, and the lowest circles contain multiple rings.

Dante and Virgil then reach the shores of Purgatory, which is guarded by Cato. The lower slopes of the Mountain of Purgatory comprise Ante-Purgatory, for souls who need to do extra penance before gaining admission to the real Purgatory. Purgatory proper has seven terraces.

As they leave the Fifth Terrace, they encounter Roman poet Statius, who accompanies them the rest of the way. Statius ranks fourth of the poem’s recurring characters, after Dante, Virgil, and Beatrice.

Finally, on Easter Sunday, Dante reaches the Earthly Paradise (the Garden of Eden) on the summit of Mount Purgatory and meets Matilda, who prepares him for his reunion with his beloved Beatrice. Dante begins crying when he realises Virgil is gone, and Beatrice rebukes him and tells him to pull himself together. For the first and only time in the poem, Dante is addressed by name.

On Bright Monday, the day after Easter, Beatrice escorts him to Paradise, composed of nine concentric, celestial spheres around Earth. Paradise is topped by the Empyrean, home to the most important saints and Biblical figures. Mary is on the top step.

Dante is able to see the light of God, and with it the perfect union of all realities and the understanding of everything in this world and the next. In the centre of this light are three circles representing the Trinity, but, being a mere mortal, Dante can only see so much.

His soul, however, perceives the harmony of the Universe, and he understands Love is the mechanism behind God, the Universe, life, and everything else in existence.

Wow, what a great summary, perfect blend of informative and entertaining. I didn’t remember (or maybe never knew) about how his son was led to the manuscript, could be a book on it’s own 🙂 good luck with the A to Z!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m learning all kinds of new details. Thanks!

Black and White: D for Dorado

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate learning the origin story of the Divine Comedy, why it’s called that, the gist of the story, and the lovely illustrations. I’m learning a lot with your posts.

My “D” Tull song is located here:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a literary classic! I’m quite familiar with the work, but I’m not sure if I’ve ever actually read it. I don’t remember reading it, but maybe I did. Guess I should read it again someday.

Arlee Bird

Tossing It Out

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved the episode of Jacopo’s dream. It’s probably a legend, but I still like it 🙂

@JazzFeathers

The Old Shelter – The Great War

LikeLike

You know, Inferno was mandatory reading for us in high school, but we were never required to read Purgatory or Paradise. I never thought about how weird that is until recently…

The Multicolored Diary

LikeLike