So many people have this idea that only the first third of The Divine Comedy is worth reading, and they treat it as the first book in a trilogy instead of understanding it’s the first of three canticles in a long epic poem meant to be read in its entirety. Do these people quit reading other multi-part books after Part I, or stop watching long films after the intermission? At least own that you DNFed them!

Here are some compelling reasons you should read the entire Commedia, the way its author intended it to be read:

1. Dante didn’t want his readers to stay in Hell or end on a sad, low, hopeless note! He and Virgil see stars when they climb out of the abyss, and the next leg of their otherworldly journey begins immediately in the second canticle. Dante wanted to take us into the heights of Paradise with him, even if he does warn readers to turn back if they’re not ready for the intense theology of the final canticle.

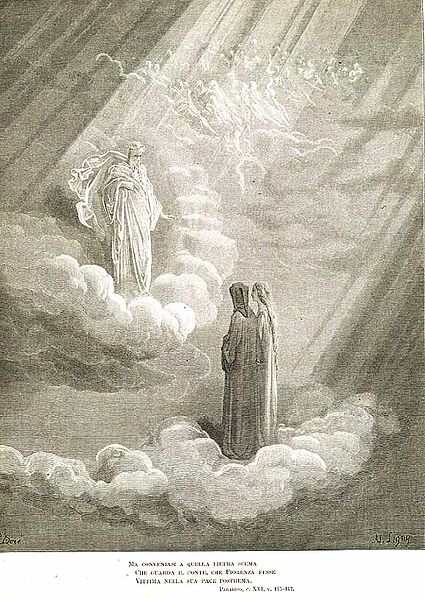

2. You’ll miss Dante’s reunion with Beatrice, one of the most powerful sections of the book. He’s not going through the afterlives for kicks and giggles. His lost love sent him on this journey to revive his faith, and possibly even save his life.

3. Virgil’s character development takes on a very interesting direction. He goes from being the steady voice of reason and totally in control in Inferno (except that one time he failed outside the gates of Dis!) to making more and more mistakes and not knowing what to do in Purgatorio. His character arc is possibly one of the most unexpected in all of literature.

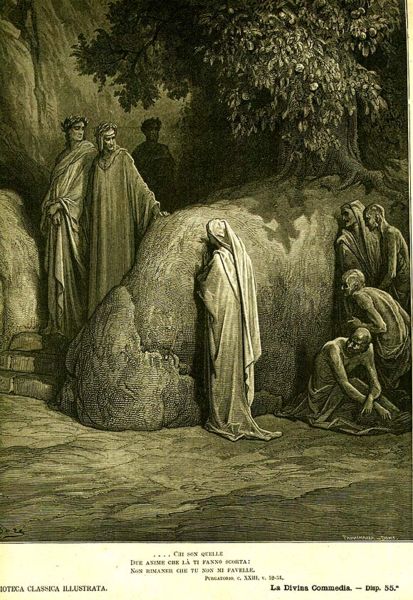

4. The relationship between Dante and Virgil deepens even further. Though they’re only together for a few days, they become as close as father and son. A number of times, Virgil is compared to a father or mother, and when Dante turns to him for comfort upon Beatrice’s entrance, the word mamma is used. He bursts into tears when he realizes Virgil is gone.

5. The poetry becomes more and more beautiful as the poem progresses. Yes, it also becomes increasingly difficult to understand and relate to as theology comes to the fore, but don’t let that put you off from the gorgeous images, sounds, and turns of phrase. This is also one of many reasons you should get a dual-language edition!

6. There’s a lot of emotion, drama, beauty, power, and tension in the second and third canticles, whereas there’s not much room for most of that in Hell.

7. You don’t want to miss the beautiful concluding cantos, particularly Dante’s tender farewell to Beatrice, St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s prayer to Mary (the one who ultimately set Dante’s journey in motion), and the unforgettable final lines.

8. Though Dante was a faithful Catholic, he nevertheless struggles with certain then-mainstream points of theology. He finally airs these doubts in detail in Paradiso. Most meaningfully to me as a non-Christian reader, he questions the teaching that only baptized Christians can attain Paradise, even if they lived long before Jesus or in places like India and Ethiopia. He says righteous non-Christians, devout in their own faiths, are closer to God than insincere Christians.

9. Dante’s treatment of women, religious minorities, and gay men continues to reflect a surprisingly modern, nuanced, sympathetic attitude lightyears ahead of his time. He’s still ultimately a product of his time and place, but his overall worldview isn’t entirely tied to the Middle Ages.

10. The entire book is a priceless compendium of history, politics, religion, and mythology. There are also many astronomical, geographical, and mathematical references and calculations. This truly was a continuation of Dante’s discontinued encyclopedia Il Convivio. Without Dante serving as the historian of record for many of these people, particularly the women, even hardcore Medieval history scholars wouldn’t know or care about them.

11. You will never fully, properly understand any book if you DNF it.

12. Many of the most touching, beautiful, memorable, poignant, and/or powerful moments happen in the second and third canticles. You’ll miss them if you only read Inferno.

13. Dante directly addresses readers seven times in each canticle, and the opening line famously says “In the middle of the journey of our life,” not “my life.” He wanted us to feel as though we’re experiencing this together, to put ourselves in his shoes as we renew our faith, hope, and priorities.