There are so many aspects of the Medieval era one needs to research and keep in mind while writing hist-fic set during this wide-ranging era. It’s so important to pin down specifics for a particular country, century, and decade. The way people lived in Italy, France, England, Germany, Russia, Sweden, and Hungary was radically different. The Middle Ages never had a one size fits all culture.

386. Because of the high cost of illuminated manuscripts and the long production time, not to mention the fact that many people were illiterate or not highly educated, history chronicles weren’t books found in most homes. Thus, the average person wouldn’t know much of anything about the history of his or her own area.

387. Even if someone did own a history chronicle, that book generally only covered the history of one country, the known ancient world, or the lives of royals, nobles, or clergy. They weren’t chronicles of the entire world!

388. Annals (live chronicles) listed historical events in chronological order and often added new events as they happened, as opposed to dead chronicles, whose recording of history stopped at the last date of writing.

389. There was much melding of mythology and history, with Medieval historians portraying events and people we now know to be purely mythological and folkloric, or at best semi-legendary, as though they were part of actual verified history.

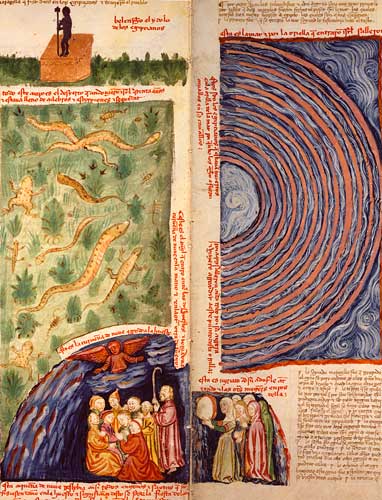

390. Many Medieval historians also wrote about fantasy creatures like dragons and griffins as though they were real animals. Bestiaries were incredibly popular books, illustrating and describing both real and imaginary animals.

391. Most Medieval chroniclers accepted what they’d heard or read as absolute fact, with no attempt to check for verification in other sources or apply any skepticism to wild claims.

392. Even if a chronicle about a foreign country were written in Latin, or a vernacular language one understood, odds are the average person wouldn’t have encountered the book or sought it out. Why would someone who wasn’t a passionate scholar, intellectual, and/or historian be interested in the history of a country s/he’d almost certainly never visit or need to know anything about?

393. Some chronicles, like The Anglo–Saxon Chronicle, were compiled by multiple people over several centuries as an exhaustive history.

394. Some chroniclers recorded what they’d personally witnessed or had direct knowledge of from their own lifetime, while others relied on older documents or oral tradition.

395. Many chronicles compiled over a long period of time were updated and corrected as new information came to light.

396. The Medieval Chronicle Society is an international organisation studying and documenting these books. They publish a peer-reviewed journal called The Medieval Chronicle, have a conference every few years, and maintain an exhaustive encyclopedia documenting the thousands of Medieval chronicles known to exist. They’re a great source for research.

397. A chronicle commissioned by a ruler had to reflect him or her, and his or her family, in the best possible light!

398. Regardless of who initiated a chronicle, historical figures and events were frequently fancified and embellished wildly.

399. It was very common for chroniclers to trace ruling houses’ genealogy to mythological figures (e.g., Thor, Zeus) and Biblical figures for whom there’s no evidence of existence.

400. It also goes without saying that just about all Medieval chroniclers believed in Biblical literacy instead of interpreting certain things more symbolically or as archetypal race memories. I personally also believe the Matriarchs and Patriarchs, Moses, and other pivotal figures of Jewish history existed, but without any historical or archaeological evidence, it’s a matter of faith. King David is the first Biblical character we know for certain really lived.

401. Chroniclers were called cronistas, and usually were employed in official government positions instead of working independently. They were often unpaid and held that role for life, and were elected by the city council in a plenary meeting.

402. Medieval chronicles didn’t attempt to interpret or analyse historical events. They just reported what happened, or what was said to have happened.

403. Though a debate about his historical existence rages today, King Arthur was very much believed to be a real person in the Middle Ages. He wasn’t definitively mentioned until ca. 828, in Historia Brittania, and was totally left out of several earlier British history chronicles. I’m inclined to believe he was semi-legendary and that we may never know for sure on account of the near-total scarcity of surviving written material from post-Roman Britain.

404. Cleopatra was widely, falsely portrayed in an unflattering light, like conducting grotesque science experiments on her slaves, constantly seducing men, and not being of much importance. Obviously, much of this historical character assassination is due to misogyny. We now know she was a strong, capable ruler and only had two lovers.

405. Another widely-believed myth was the Donation of Constantine, an eighth century forgery purported to have been written in the fourth, in which Emperor Constantine transferred authority of Rome and the western part of its empire to the Pope. This fake document played a huge role in the Investiture Controversy, a church and state conflict between the Papacy and secular rulers.

406. Due to a Medieval misunderstanding of history, Prophet Mohammad was falsely believed to have originally been a Nestorian Christian and therefore a heretic and schismatic. He was also condemned as an Antichrist, pervert, false prophet, and degenerate. Thankfully, interfaith relations have come a huge way in the last thousand years! There are certainly legit criticisms of him and controversies that may never be resolved, but we do know for sure he was never any type of Christian.

407. On the Muslim side, there was no ban against depicting Prophet Mohammad in artwork during the Middle Ages! After 1500, it became more common to show him with a blank face like an Amish doll, a veil over his face, or with Divine flames in place of a face, though more than a few artists continued depicting him in fully human form.

408. Pope Anastasius II (d. 498) was falsely believed to be a heretic and apostate, based on his efforts to try to end the Acacian schism between East and West. His sudden death was also believed to be Divine punishment for daring to try to mend the schism. Modern historians have rehabilitated his reputation and called out the Medieval attacks on his character.

409. Many clergy and monks produced histories and chronicles, both religious and secular. Common subjects were wars (esp. the Crusades), Church history, politics, and biographies. Monasteries were among the few places in Europe with historical archives, though there wasn’t much of an organisational system to enable easy access to the specific information desired. Many archives were also closed to non-community members.

410. Very learnèd people may have read chronicles from other countries, but those countries wouldn’t have included places like China, Japan, Korea, sub-Saharan Africa (many of whose peoples didn’t yet have writing systems), or Sri Lanka!