To mark Yom HaShoah 2024, I decided to discuss the importance of Holocaust historical fiction. I don’t understand people who get their knickers in a knot and rant about how it’s automatically offensive, grotesque, sensationalistic, and inaccurate. One of the hallmarks of hist-fic is putting fictional characters in real-life events and showing how they live through it. There’s no rule that hist-fic should only be about shiny, happy moments in history or that there are certain events that can only be in the realm of nonfiction.

Here’s an idea: If you’re so genuinely triggered or traumatised by books and films about the Shoah, 9/11, the Second Intifada, or other very tragic events you lived through, have generational trauma from, or just find generally upsetting, you can choose not to read or watch them. No one is forcing you to do that. But you don’t get to dictate what other people choose to write about.

We’re living in a time when more and more Holocaust survivors are leaving us every year. As of January 2024, there were only 245,000 left. The oldest known living survivor is 112, and the youngest, who were born during the war and survived in hiding or camps like Bergen-Belsen and Terezín, are almost 80. Most of the remaining survivors were children, not adults.

Hence, we won’t have infinite firsthand testimonies and memoirs forever. Eventually, any new books will have to be historical fiction or nonfiction. As long as a fictional story is told respectfully and strives for the utmost accuracy, I don’t see any problems.

It’s also important to combat Holocaust denial. If it’s this bad while we still have living survivors, just imagine how much more insidious it might be when the last first-person witness is gone.

I’ve written before about how to research this subgenre, and why accuracy matters so much. Here are some more things to keep in mind, and original angles to research:

1. So many people bleat about how all WWII/Shoah books are the same story over and over again, just with different names and details. Why not counter that by setting your book in a country rarely, if ever, covered in memoirs and hist-fic? E.g., Greece, Bulgaria, Estonia, Norway, Luxembourg, Serbia, Albania, Slovenia, the Channel Islands.

2. Though most people only think of the Shoah as happening in Europe, North African Jews in Algeria, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia also faced persecution and deportation to camps under Nazi and Italian occupation.

3. No two people experienced the Shoah in the same way. Your story doesn’t have to be set in a camp or ghetto to be a “real” Holocaust story. E.g., many children went to the U.K. on the Kindertransport, while other people escaped to neutral countries or open cities like Shanghai. Some people went into hiding or managed to live publicly under a pretended Gentile identity.

4. The camps people were shipped to weren’t random! It would make no sense for, e.g., someone in France to go to Janowska near Lviv, or for someone from Greece to go to Klooga in Estonia. You also need to know dates of founding and evacuation.

5. Very few children were allowed to live at death camps, unless they were being used for medical experiments, in the Czech and so-called Gypsy family camps of Auschwitz, arrived during a rare gas malfunction or after gassing stopped, or chosen for a rare position like a messenger boy or girl. Children who lied about their age also had to look it.

6. As Dara Horn proves in her brilliant, deliberately provocatively-titled essay collection People Love Dead Jews, too many Shoah stories are sugarcoated for a Gentile audience and given a warm, fuzzy moral about loving everyone and a generic lesson about man’s inhumanity to man. Holocaust education is such an embarrassing failure when people believe it arose out of nowhere instead of being the culmination of almost 2,000 years of European antisemitism, and thus a uniquely Jewish tragedy.

7. Unless you live in Poland and are subject to the ridiculous Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance, you don’t need to use the goofy, totally nonintuitive, wordcount-bloating phrase “German Nazi-occupied Poland.” Normal people understand the name Poland as a geographical reference, not blame for running the camps. Even memoirs by Polish-born people themselves don’t use that silly term!

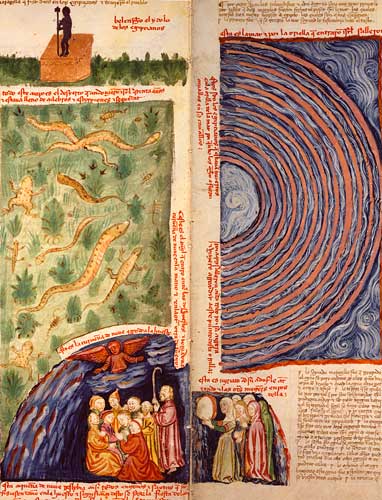

Children’s Memorial at Yad Vashem

8. Widely read multiple sources while researching! I had to majorly retool my Hungarian characters’ stories because I assumed Isabella Leitner’s searing, haunting memoir was representative of all Hungarians’ experience. Through watching lots of USC Shoah Foundation interviews and doing more reading, I found out most people were registered for work in the main camp or transported to labor camps and factories instead of languishing in Lager C doing almost nothing for six months, before being sent to dig tank traps in the woods.

9. Any escapes (from a camp, ghetto, mass grave, etc.) need to be plausible. Read about real-life escapes and how they were successfully pulled off.

10. There were no escapes from gas chambers! A handful of people managed to survive because they were on the bottom, but they were sadly murdered upon being discovered. The only people who went in and walked out unharmed were there during RARE gas malfunctions.

11. It’s easier to stick fictional characters in camps with large populations. If a sub-camp had only a few dozen inmates, those people would be well-documented, and any fictional people would stand out in that small real group.

12. Above all, don’t forget how bonds of love flourished even in the most bestial of circumstances. So many people survived for one another, because of one another.