Welcome back to Weekend Writing Warriors and Snippet Sunday, weekly Sunday hops where writers share 8–10 sentences from a book or WIP. The rules have now been relaxed to allow a few more sentences if merited, so long as they’re clearly indicated, to avoid the creative punctuation many of us have used to stay within the limit.

I’m switching back to A Dream of Peacocks, my alternative history about Dante and Beatrice. This comes from near the beginning of Chapter XIX, “Beautiful Betrothal.” It’s now late September 1288, and Dante and his much-younger halfsiblings have been staying at the Portinaris’ summer villa in Fiesole since July. They’ve postponed their return to Florence because Beatrice is recovering from a long, serious illness, a brutal beating from her now-deceased husband, and a birth that almost killed her.

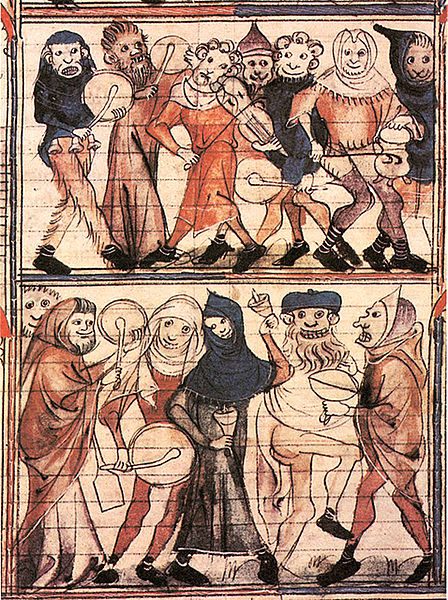

Folco Portinari, father of Beatrice

I was reading Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics in an anteroom off of the great hall when I became aware of Ser Folco calling my name. With much reluctance, I closed the book and set it on a small table on my left. Respect for my host came before everything, even my beloved Aristotle.

Ser Folco took a seat on a golden-backed chair with scarlet velvet cushions. “I’ve been seriously thinking about a very important subject for the last few months, which we need to discuss. If you don’t agree with my suggestion, I won’t feel offended or insulted. I also won’t mind if you need some time to think about this before you give an answer. We’ll still be friends regardless.”

I suspected he wanted to talk about money, and began silently rehearsing how I’d politely refuse his charity. It was one thing to stay in his villa and accept some money and other generous gifts every so often, but it would be humiliating to entirely exist on charity.

The ten lines end there. A few more follow to finish the scene.

People already talked about how I had to beg for so many loans and the financial trouble my family had fallen into. They didn’t need any more reasons to laugh and disrespect me.

“What happened last November was a tragedy,” Ser Folco began. “I can’t begin to imagine what it’s like to lose my wife so young and unexpectedly, and to lose a firstborn son before his life began. That obviously deeply affected you, and I’m glad you seem to be past the worst of your grief.” He paused before continuing. “You’re too young to live the rest of your life as a childless widower. It’s not good for man to be alone, and it’s our duty to have as many children as possible. Have you considered remarriage yet?”

Thank God, he wasn’t going to insult me by offering charity. “Of course I’ve thought about it, but I had far more important priorities over the last year, coupled with how I couldn’t leave my house for most of that time. Do you have a second wife in mind for me?”

Ser Folco smiled. “Indeed I do. I’ve discussed this potential marriage with Cilia, and she agrees with me that it couldn’t be more perfect. Would you be at all interested in Bice?”