Xuetes, also called Xuetons and Chuetas, live on the Spanish island of Mallorca, part of the Balearics, in the Mediterranean Sea. In Balearic (the collective name for the various Catalan dialects spoken on the islands), the word xueta derives from juetó, which in turn is a diminutive of jueu (Jew). The word xuetó has the same meaning. Many Old Spanish and Catalan words and names used X instead of J.

Other linguists believe it derives from xulla, a type of salted bacon, and, more generally, pork. Since the original Xuetes were forcibly converted to Christianity, they felt compelled to publicly eat pork to prove themselves. There was also a tradition of using derogatory words for pork to refer to Jewish converts; e.g., Marranos.

Because of the offensive original etymology, Xuetes prefer the terms del Segell (a street many of them lived on), del carrer (of the street), noltros (we), or es nostros (us).

Church of Montesión (Mount Zion) in capital city Palma de Mallorca, once a synagogue but now the Xuetes’ main church; Copyright Drozi Yarka, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Because of their religious and ethnic origins, the Xuetes have been stigmatized and segregated for much of their history. In addition to being rejected by the outside world, they also felt it very important to keep their true heritage alive by only marrying other Xuetes. Between 18,000–20,000 Xuetes, there are only fifteen surnames—Aguiló, Bonnin, Cortès, Fortesa, Fuster, Martí, Miró, Picó, Pinya/Piña, Pomar, Segura, Tarongí, Valentí, Valleriola, Valls.

Many other surnames in Mallorca have Jewish origins (e.g., Amar, Homar, Maimó, Salom, Jordà, Daviu), but not all Conversos are Xuetes. Only a very small, specific group of families have that verified ancestry, and many Xuetes don’t know the full history of their own group.

A social stratification has existed since their pre-conversion era, though it became much stronger in the late 17th century. People higher up on the socioeconomic scale are orella alta (high ears), while those lower down are orella baixa (low ears).

Church of St. Eulàlia, Palma de Mallorca, Copyright Steffen Schmitz (Carschten) / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE or Free Art License

Xuetes practise a hybrid of Judaism and Christianity called Xueta Christianity. Their primary churches are Montesión and St. Eulàlia; the former was once the city’s main synagogue.

To save their remaining community from murderous pogroms or expulsion, the Jews of Mallorca agreed to a mass “conversion” in 1435. This was done out of psychological duress and pikuach nefesh (saving a life taking precedent above all else), not genuine religious belief.

The Inquisition came to town in 1488, much to the entire population’s complaint and opposition. Their pleas fell on deaf ears, and the repressive thugs drunk on their own power got to work rooting out and severely punishing “insincere” converts who still privately practised Judaism.

By 1544, a total of 537 people had been turned over to authorities to be burnt at the stake, though 455 managed to escape and were burnt in effigy. The remaining 82 were executed.

In 1632, Count Juan de Fontamar, prosecutor at the Mallorcan court, sent a scathing report to the Supreme Inquisition, in which he levelled 33 charges against the island’s Conversos. Most were related to how they still practised Judaism and Jewish culture. Because the Inquisition had much bigger fish to fry at this point (such as the Protestant Reformation and corrupt clergy), they didn’t pursue the matter.

Around 1640, the Xuetes’ economic fortunes began a marvellous upwards rise, with many more jobs opened to them. Because many of them went abroad for business or dealt with people from abroad, they came into contact with Jewish communities in places such as Livorno, Amsterdam, Rome, and Marseille. Through these relationships, they began reading Jewish literature and religious texts.

Montesión, Copyright Enric, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

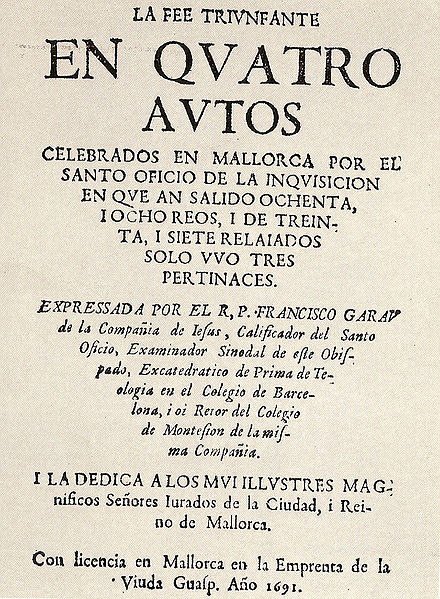

For unclear reasons, the Inquisition returned in 1673 and kicked back into high gear. Their first victim was Isaac López, a 17-year-old on a ship of Jews expelled from Oran and stopping in Mallorca. He refused to “repent,” and was burnt at the stake in 1675.

The Inquisition Tribunal, Francisco Goya, 1812–19, depicting the garments and hats Inquisition victims were forced to wear

Five autos-da-fé took place in spring 1679, after authorities razed and salted the earth of a building and garden where many Conversos met. Hundreds of people were imprisoned, tortured, severely punished, and murdered.

On 7 March 1688, a large group of Conversos sneaked onto an English ship to escape, but stormy weather ruined their plans, and they returned home. As soon as the Inquisition learnt of their attempted escape, they were all arrested. Their trials lasted three years.

The final person condemned to death by the Mallorcan Inquisition, Gabriel Cortès, was burnt at the stake in effigy in 1720.

Instead of being “scared straight” and renouncing their Jewish origins, the Xuetes’ sense of community and faith were strengthened by the Inquisition. It also inspired them to fight for equal rights and forge political alliances with the nobility and clergy. The descendants of many other Conversos on Mallorca, meanwhile, lost all connection to and knowledge of their ancestry.

Though they remain a people apart, Xuetes have gained much more respect, rights, and recognition in both Mallorca and Spain in recent decades. They’ve also been formally recognised as halachically Jewish, and some Xuetes have returned to the faith of their ancestors.

I’ve never heard of this before. It parallels the persecution of Huguenots in France at about the same time. And the fact that ‘Jews of Mallorca agreed to a mass “conversion” in 1435. This was done out of psychological duress and … not genuine religious belief’ reminds me of the forced abjurations.

LikeLike

Another piece of history I’m learning only because of you. Thank you. Alana ramblinwitham

LikeLike