St. Vladimir, Grand Prince of Kyiv (ca. 958–15 July 1015), was the sixth Ryurikovich ruler of Kyivan Rus. He was the youngest son of Prince Svyatoslav and his servant-turned-wife Malusha.

In 969, Svyatoslav moved his capital to Pereyaslavets (modern-day Nufǎru, Romania). To his oldest son, Yaropolk, he gave Velikiy Novgorod (Great Novgorod), and to Vladimir he gave Kyiv.

Svyatoslav was slain by Pechenegs in 972, and in 976, a fratricidal war erupted between Yaropolk and his younger brother Oleg, Prince of the Drevlyans (an East Slavic tribe). After Yaropolk killed Oleg in battle, Vladimir fled to their relative Haakon Sigurdsson, Norway’s ruler.

Haakon sent many warriors to fight against Yaropolk. When Vladimir returned from Norway the next year, he marched against Yaropolk.

On his way to Kyiv, Vladimir sent ambassadors to Prince Rogvolod of Polatsk (an ancient East Slavic city) to sue for the hand of his daughter, Princess Rogneda (962–1002), who was engaged to Yaropolk.

When Rogneda refused, Vladimir attacked Polatsk, raped Rogneda in front of her parents, and murdered her parents and two of her brothers.

Vladimir secured both Polatsk and Smolensk, and took Kyiv in 978. Upon his conquest of the city, he invited Yaropolk to negotiations at which he was murdered.

Vladimir was proclaimed Grand Prince of all Kyivan Rus.

Vladimir expanded Kyivan Rus far beyond its former borders. He gained Red Ruthenia (Chervona Rus), and the territories of the Yatvingians, Radimiches, and Volga Bulgars.

He had 800 concubines, and at least nine daughters and twelve sons from his seven legitimate wives.

![]()

Though Vladimir’s grandma Olga had converted to Christianity and begun Christianizing Kyivan Rus, Vladimir was an unrepentant pagan. He erected many statues and shrines to pagan deities, elevated thunder god Perun to supreme deity, instituted human sacrifices, destroyed many churches, and murdered many clergy.

When a Christian Varangian named Fyodor refused to give his son Ioann for sacrifice, a mob descended upon his house. Fyodor and Ioann, both seasoned soldiers, met the mob with weapons in hand.

The mob, realizing they’d be overpowered in a fair fight, smashed up the entire property, rushed at Fyodor and Ioann, and murdered them. They became Russia’s first recognized Christian martyrs.

Vladimir thought long and hard about this. In 987, he sent envoys to study the major religions and report back on their findings. The envoys also returned with representatives of these faiths.

Vladimir rejected Islam because he couldn’t give up pork or drinking, and didn’t want to be circumcised. He rejected Judaism because he felt the destruction of Jerusalem was “evidence” we’d been “abandoned” by God.

Vladimir found no beauty in Catholicism, but was very impressed by the beauty of Orthodox Christianity.

Vladimir agreed to become Orthodox in exchange for the hand of Anna Porphyrogenita, sister of Emperor Basil II of Byzantium. (Porphyrogenita, “born in the purple,” was an honorific for someone born to a Byzantine emperor after he’d taken the throne.)

Kyivan Rus and Byzantium were enemies, but after the wedding, Vladimir agreed to send 6,000 troops to protect Byzantium from a rebels’ siege. The revolt was put down.

Upon his return to Kyiv, Vladimir compelled his subjects into a mass baptism in the Dnepr River, and burnt all the pagan statues he’d erected.

![]()

After the mass conversion, Vladimir formed a great council from his boyars, gave his subject principalities to his twelve legitimate sons, founded the city of Belgorod (Bilhorod Kyivskyy), and embarked on a short-lived campaign against the White Croats.

Though his conversion was politically motivated, Vladimir nevertheless became very charitable towards the less fortunate. He gave them food and drink, and journeyed to those who couldn’t reach him.

He married one final time, to Otto the Great’s daughter (possibly Rechlinda Otona).

In 1014, he began gathering troops against his son Yaroslav the Wise. They’d long had a strained relationship, and when Yaroslav refused to pay tribute to his brother Boris, heir apparent, it was the last straw.

Vladimir’s illness and death prevented a war. His dismembered body parts were distributed to his many sacred foundations and venerated as relics.

Several cities, schools, and churches in Russia and Ukraine are named for Vladimir. He also appears in many folk legends and ballads. His feast day is 15 July.

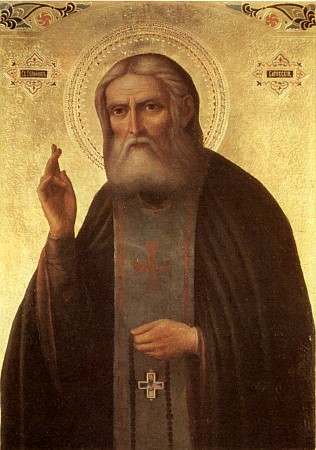

An ikon of St. Vladimir is one of the things my character Ivan Konev throws into a valise before he escapes into his root cellar to hide from vigilante Bolsheviks who’ve broken into his house in April 1917.

That ikon becomes very dear to Ivan and his future wife Lyuba. They believe Vladimir protected them during the Civil War. When their oldest son Fedya goes to fight in WWII, they lend him the ikon.